Last night I dreamt of Jack. In the dream I was telling people about him, reading through our old messages and emails. God, it hurt. But maybe it was Jack himself, prodding me: “Weren’t you going to put this post up a week ago, Mary?”

He and I called each other “Mary” because of our shared obsession with Jesus Christ Superstar (and because we both wanted to play that role). We met 10 years ago, on a panel at a writers’ festival. Jack won over the audience with his warmth and the occasional violent role roll across the stage, dressed in what I’m sure was a bow tie and sequinned dinner jacket. He closed the night with a moody duet of The Motels’ Total Control with Ella Hooper. I want to know that guy, I thought.

Everybody wanted to know him, as it turned out. Everyone counted Jack as their best friend and had their own nickname. That’s cool – the sheer numbers could never have diminished his affection for each of us.

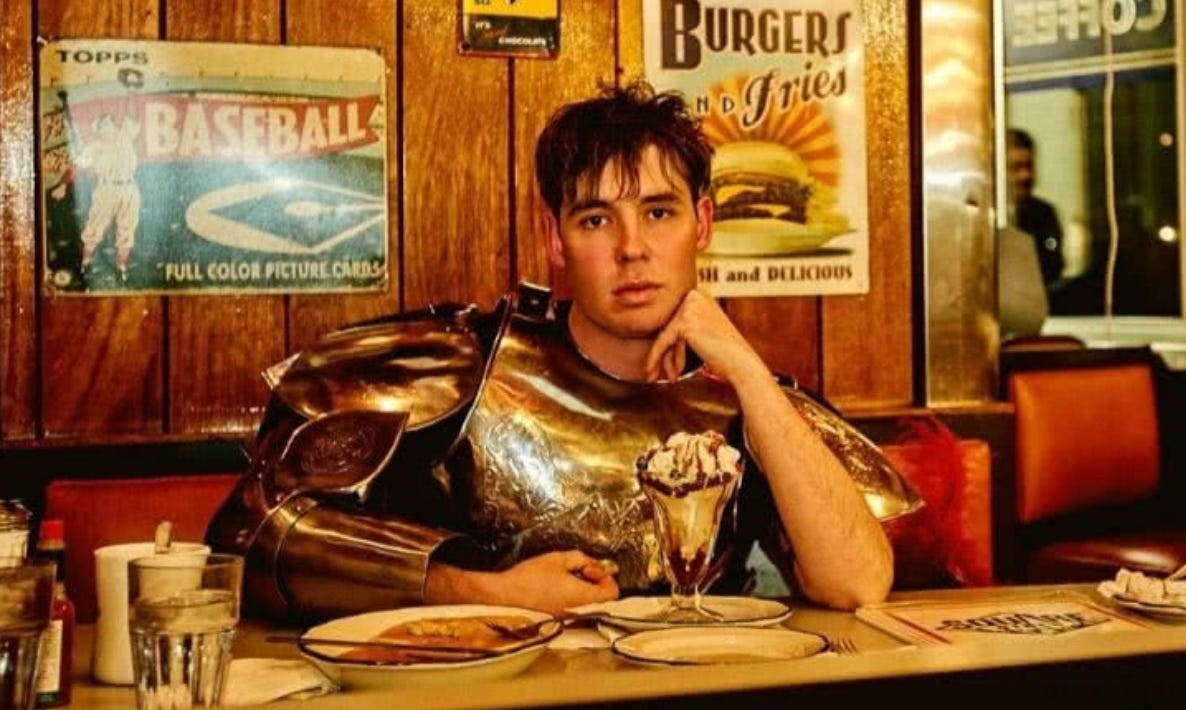

Live, he was a one-man séance, cresting operatic highs and frightening the horses with guttural, primal lows. Visually, he was a vision board of romantic leads, from a knight in shining armour eating an ice-cream sundae, to a shirtless dreamboat swooning into a bed of flowers. On record, through his cluster of EPs and singles, his work as a music director, and on his 2020 debut album Swandream, he tackled darkness head on.

Jack died six months ago. I took that above paragraph from The Guardian obituary I wrote. The obit took on a weird life of its own when other news sites picked it up, some of which have audiences not generally known for being into provocative, sensitive, queer musicians. I feared what their comment sections would say, but actually, the hundreds of comments were more concerned with hijacking this 34-year-old’s death for their own ghoulish agenda, claiming him as another young man who died from ‘the jab’.

Untrue.

So I was pleased when, last week, Jack’s close friend – the writer Sam Twyford-Moore – went on Marieke Hardy’s Going to Die podcast and talked honestly and empathetically about Jack’s suicide, and the childhood traumas and mental health struggles he had endured.

Like so many of his peers, Jack also faced an uphill battle in being a fiercely independent artist in Australia. Oftentimes our messages lamented that “no one cares”. And then he’d shake us out of it. “I feel something good is around the corner,” he wrote. But things were tough.

Actually, here’s Jack talking to the ABC about how his last album was basically therapy:

Jack’s trauma and creativity were innately intertwined. On the Going to Die podcast, Sam quoted Ethan Hawke, who had said of the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman and Robin Williams and their talent: “it didn’t come for free”.

Jack wrote for the Guardian about crying “big lonesome tears” to the work of tortured genius Daniel Johnston. He loved strong female artists. His queen, the patron saint of lost boys and girls, was Tori Amos, and he’d play piano like her, half-facing the audience. As Jack wrote for Kill Your Darlings, about the time he finally met Tori:

“I wanted to tell her that I had allowed her music to save my life during a time when I saw no way out. When you yourself are a teenager struggling with your sexuality, who was also raped by a stranger, listening to the work of Tori Amos can be pretty powerful stuff.”

But Jack did for a new young audience what Tori did for him: became a lifeline.

Like so many artists, Jack had to stretch himself thin chasing different revenue streams; our phone calls were always squeezed in while he caught buses all over Sydney to teach kids guitar, piano and singing. He was also music director for the joyful Polyphony Choir in Sydney, often conducting in a glittery cape or leather chest harness. The choir brought a huge group of disparate people together, helping them find home, and find a family. I’m so heartened to hear that they’re still going.

I know a little about how the choir might be feeling now. In 2015, I organised a concert in the newly minted Amphlett Lane in Melbourne, and Jack came on board without hesitation as choirmaster. (Years earlier he’d worked in a café in Surry Hills and had fond memories of Chrissy Amphlett being sweet to him.) He arranged Divinyls songs into four-part harmonies and worked tirelessly coaching 12 lead singers in this tricky a cappella. As our conductor on the night, his face, always animated, was the ballast we needed. Afterwards, he presented me with a vinyl Divinyls album, signed by everyone, even though it was he who had done the lion’s share of the work.

Jack’s memorial in Sydney was booked out, which everyone agreed that – as a starving musician with a love of the spotlight – he would have been thrilled about.

‘Jack would have ...’ was becoming the phrase of the day.

During the service, the Polyphony Choir filed on stage, clutching flowers. The song was ‘Mysteries’, by Beth Gibbons and Paul Webb. It begins with the protagonist declaring how much they adore life. Many of the choir members crumbled and started to cry. It was annihilating. Particularly as it was so awful that Jack wasn’t there in his usual spot, at the front, to conduct them. A Mexican wave of grief ran from stage to stalls and I felt that hot moment of shame when you realise that you are not controlling your emotions in public. But the mass loss of control almost was almost as powerful as the music itself.

Afterwards, some of us went to dinner at a pub, to eulogise Jack. We talked about the way he signed off every message with LOVE YOU. Over pizzas, we started saying it to each other, face to face, at first in an unblinking challenge, then more seriously. Later, the LOVE YOUs continued, through our messages, as we dispersed through the night to different suburbs and cities.

At the time of his death, Jack had just finished recording his second album, produced by Laura Jean, and having heard the raw files I can vouch for its beauty. It’s our hope that it will be posthumously released. In the meantime, I’ll remember him in the streets of Glebe where he lived, in Manly, where we’d take walks along the shoreline, in Surry Hills, in the city, in the jacaranda-lined streets of Erskineville where I stayed the night of his memorial, and in the Botanic Gardens, where I imagine him walking as a wide-eyed student of the Sydney Conservatorium.

LOVE YOU JACK.

Further linkin’

Jack’s former partner, manager and close friend till the end, Dan Stapleton, has created an archival Instagram account for Jack and also a website, from which you can buy some incredible bubble-gum-pink merch.

Great stuff, Jenny.

What a person.

I didn’t know of him and now I do.

A big life he lived.